Think back to when you first decided to become a secondary mathematics teacher. Now recall your reaction when you learned how much mathematics you had to take to complete the degree. Often preservice mathematics teachers contemplate entering the profession thinking, “Well, I’ve been through high school math so becoming a math teacher shouldn’t be too difficult. After all, it only involves learning how to present the mathematics I already know.”

When listening to university students talking in the hallways, it is not uncommon to hear comments such as, “Why do I have to take Abstract Algebra, I’m never going to teach this stuff to high school students?” Lurking in the background is the assumption that they have a deep knowledge of the mathematics that makes up the secondary curriculum. Unfortunately, most high school students’ perception of algebra involves symbol manipulations and memorized formulae and algorithms. In order to address the underlying structure of mathematics, we will examine a basic skill that is taught in the secondary schools from an advanced standpoint.

Subsection 4.3.2 Inverse and Algebraic Structure

Now that we have started to reflect on our own experiences with inverses, we need to spend a little time exploring inverses beyond the elementary operations of addition and multiplication. While these early experiences ground us in similar patterns of behavior of sets of numbers with each operation, we need to branch out to other sets of object and operations in order to begin to abstract these behaviors and not worry about the context in which they live. After all, Poincaré expressed this so well.

Mathematicians do not study objects, but relations among objects; they are indifferent to the replacement of objects by others as long as relations do not change. Matter is not important, only form interests them. — Henri Poincaré.

As we saw in Tim’s class from

Activity 4.3.5, Kat was frustrated by the response she received from Tim when her expectation of obtaining a 1 when composing a function and its inverse did not occur. In addition to this, Mia tried to explain her understanding of inverse by stating, "Wouldn’t that just be like the flip of a function?". To which Tim smiled and responded, "No, that’s a common mistake. This is completely different when it comes to functions." Instead of taking these two responses and noticing the commonality (both students seemed to be thinking of multiplication as the operation), Tim shut them down as if what they are about to learn with respect to inverse functions is a new concept. Pirie & Kieren would see the students’ responses as an opportunity to fold back to more familiar sets and operations where the students have comfort and build toward abstraction by prompting the learner to explore the underlying structure inherent in the behavior common to addition, multiplication, and function composition. To help us frame our discussion, let’s take a little mathematical detour and explore the same structure we noticed before we defined a

group. Only this time, we will use sets of functions and our operation will be

function composition,

\(\circ\text{.}\)

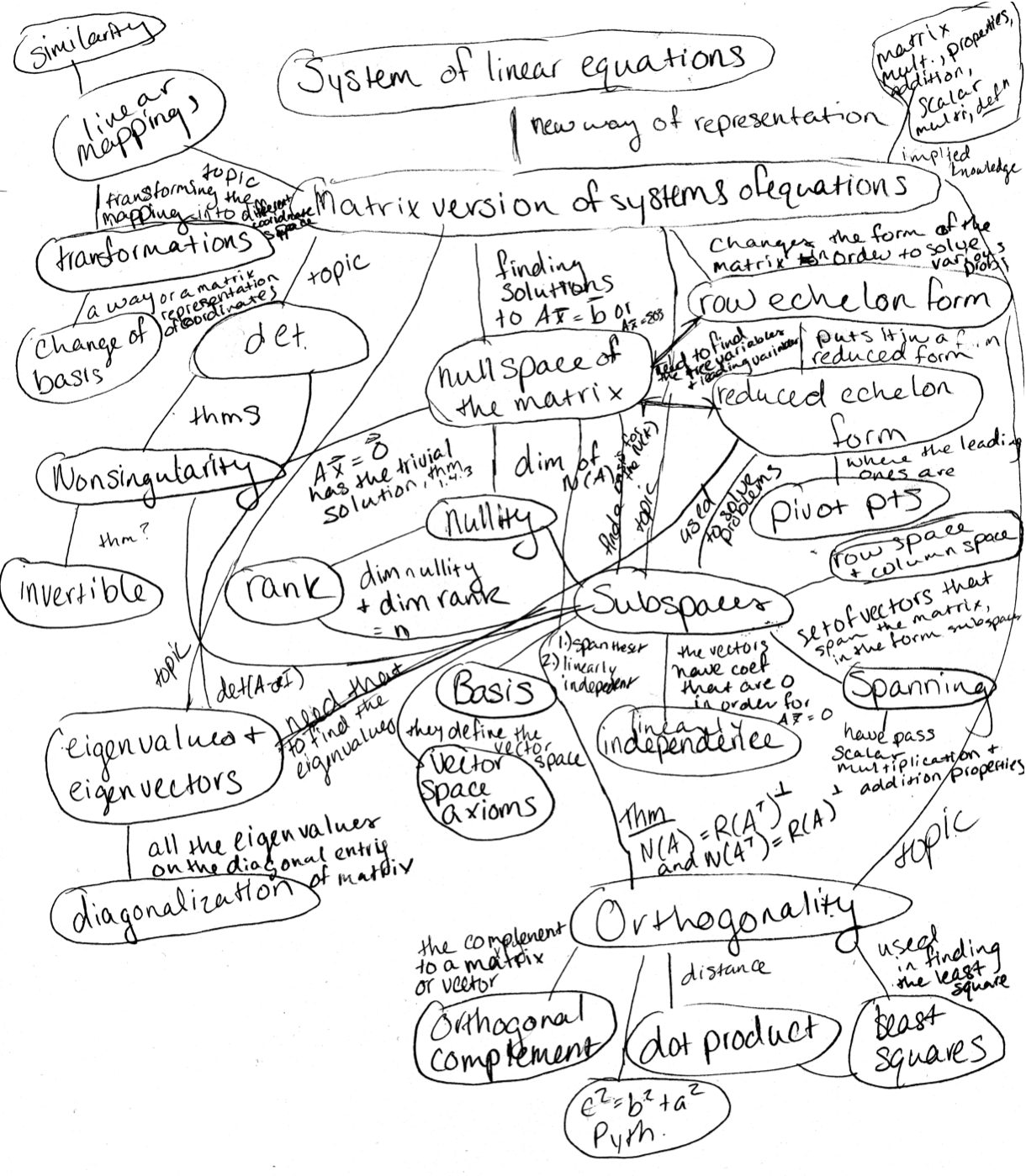

Activity 4.3.6. Form and Function.

This activity explores basic concepts of algebra including properties of algebraic structure. In high school, the primary operations used in algebra were multiplication and addition. Are these the only types of operations that can be used? We will explore this question and look for patterns that are common across algebra.

Recall that in your experiences in elementary school, you first learned to operate on the set of integers, \(\left\{\ldots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots \right\}\text{,}\) using a simple operation, addition. When this set was combined with the operation of addition, certain properties held. Some of these properties included: closure, associativity, the existence of an identity element, and inverses.

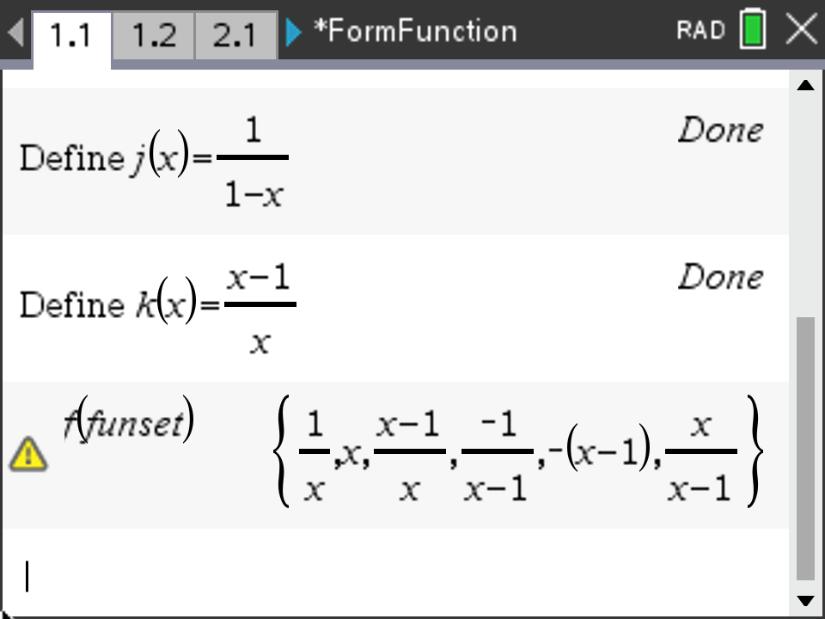

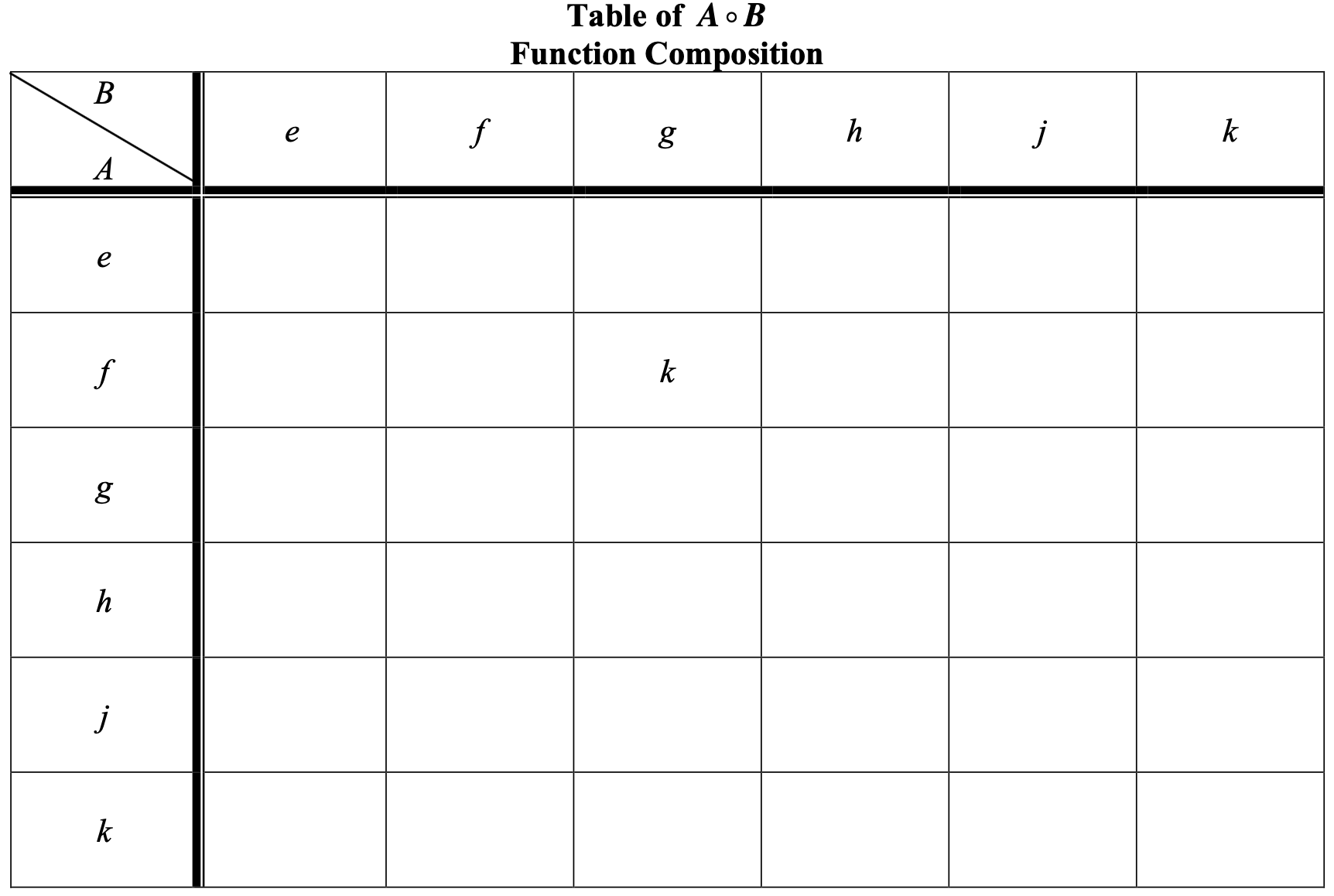

Consider the set of functions, \(T=\left\{e, f, g, h, j, k\right\}\text{,}\) where the functions are defined as follows:

Mathematics can be described as the study of patterns. For this reason, we often look for similar structure in both nature and mathematical systems. Mathematics can certainly be used to study patterns in the physical world, but we can also look for patterns within mathematics itself. Are there times when one mathematical system is, for all practical purposes, “identical” to another mathematical system and therefore governed by the same properties and relationships? If this is so, then one system can give us quite a bit of information about another system. In fact, if one system is easier to operate on, we can use it instead and then deduce information about the other system without having to do more difficult computations.

In this activity, we will explore what properties exist when pairing the set \(T\) above with the operation of composition of functions, \(\left(T,\circ \right)\text{.}\) As you explore this set, try to keep your eyes open for patterns in the relationships among functions. Some properties you may want to check might include: closure, associativity, identity, inverses, and commutativity. For example, consider your experience with basic arithmetic. For addition on the set of integers, the set is closed since adding two integers always results in another integer. The number 0 acts as an identity (i.e. \(a+0=0+a=a\text{,}\) leaving other elements unchanged) and 5 and -5 are inverses of each other (i.e. \(5+^{-}5=0\text{,}\) where combining them yields 0, the identity). This type of structure is very important for deducing mathematical truths within a mathematical system.

(a)

In general, is the set \(T\) closed under the operation of composition of functions? In other words, when performing the operation on any two elements of the set, do you always get a result that is also an element of the set? If not, what elements yield an element not in \(T\text{?}\)

(b)

Recall that the associative property states that for any three elements under the operation, say \(*\text{,}\) \(a*\left(b*c\right)=\left(a*b\right)*c\text{.}\) How might you check associativity? How many different permutations of these functions would you need to check to be certain of associativity? Devise a plan to check associativity. Your plan might include other groups from the class (divide and conquer is often very effective).

(c)

Is there a function from the set that acts like an identity element? If so, what is the function?

(d)

Does every element have an inverse? If so, list all elements and their inverses. If not, list all elements that do have an inverse along with their inverse element.

(e)

Recall if a set along with an operation meets the four criteria of closure, associativity, an identity element, and all elements have inverses, then we call the set a group. Does this set of six functions under the operation of function composition form a group?

(f)

In general, do the elements of the set commute with each other? In other words, do you always get the same result when combining any two given elements in either order (commutativity)? If all of the elements of a group commute with each other, then the group is called abelian. If a group is abelian, what kind of symmetry would you see in its Cayley table?

(g)

If the group is not abelian, for each element of \(T\text{,}\) find all elements of \(T\) that do commute with it. In other words, find all elements of \(T\) that commute with \(e\text{,}\) then all elements of \(T\) that commute with \(f\text{,}\) then all elements of \(T\) that commute with \(g\text{,}\) …etc. Here you might want to use the Cayley table you created earlier along with your answer regarding the symmetry of the table for commutativity from part (f). We call each of these sets the centralizer of the element, denoted \(C\left(e\right)\text{,}\) \(C\left(f\right)\text{,}\) \(C\left(g\right), \ldots\text{.}\)

(h)

Now list all of the elements that the sets you found in part (g) have in common. In other words, find \(C\left(e\right) \cap C\left(f\right) \cap C\left(g\right) \cap C\left(h\right) \cap

C\left(j\right) \cap C\left(k\right)=\bigcap\limits_{a \in T} C\left(a\right)\text{.}\) Since each of these elements must commute with each and every element of \(T\) in order to be in the intersection, we call this special set of elements that commute with each other the center of \(T\) and denote it by \(Z\left(T\right)\text{.}\)

If a group would be abelian, what elements would be in its center?

(i)

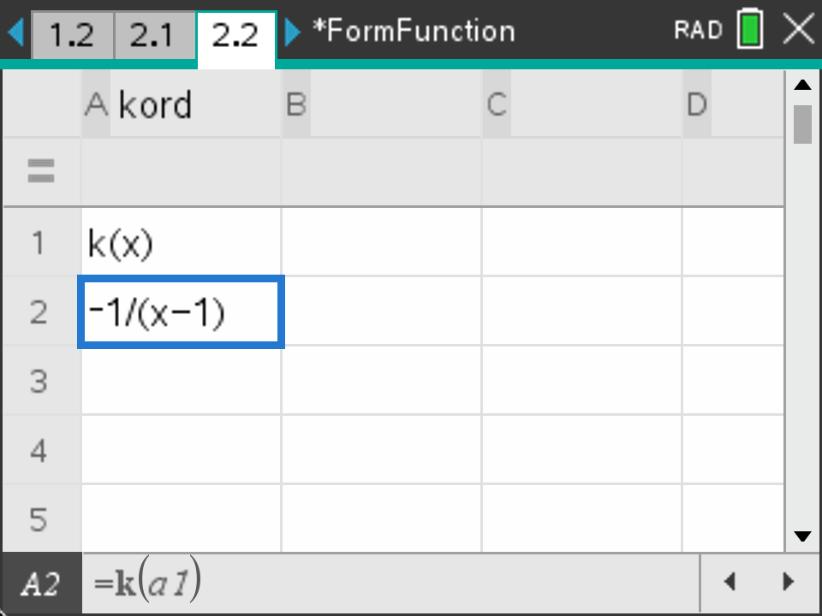

On the Calculator page (page 2.1) of your CAS, if \(k\left(x\right)=\frac{x-1}{x}\text{,}\) find \(k^5\) if it is defined by \(k^n=\underbrace{k\circ k\circ k\circ \cdots \circ k}_\text{n times}\text{.}\) Note that a “power” here is not the usual “repeated multiplication”, but instead repeated composition of functions.

(j)

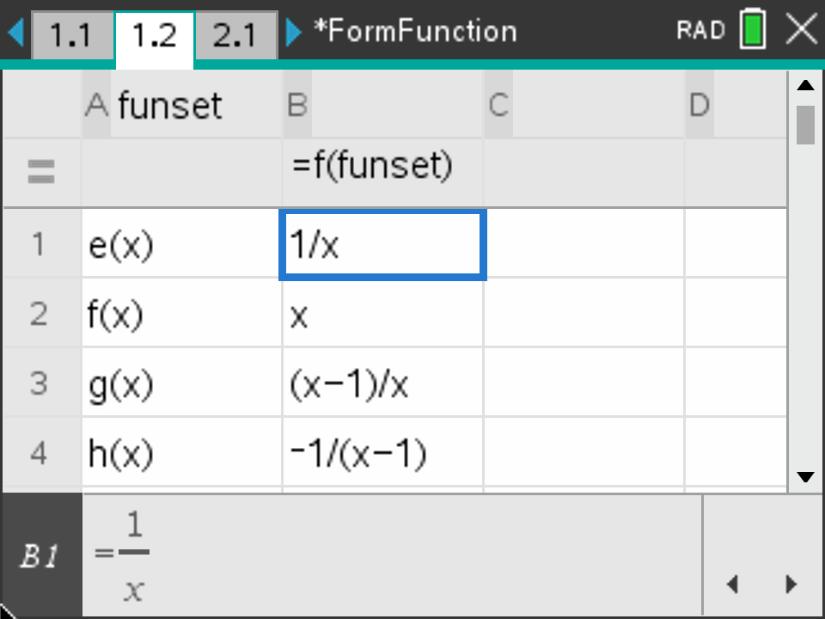

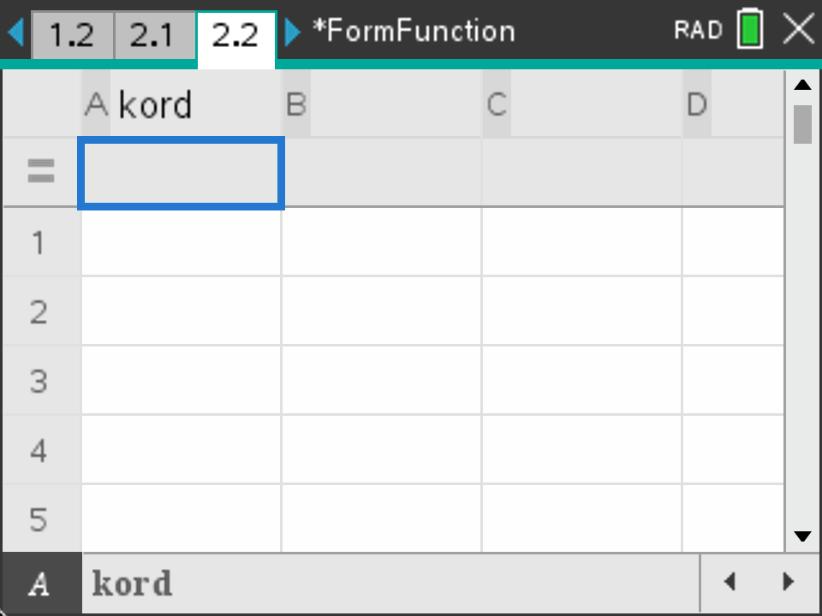

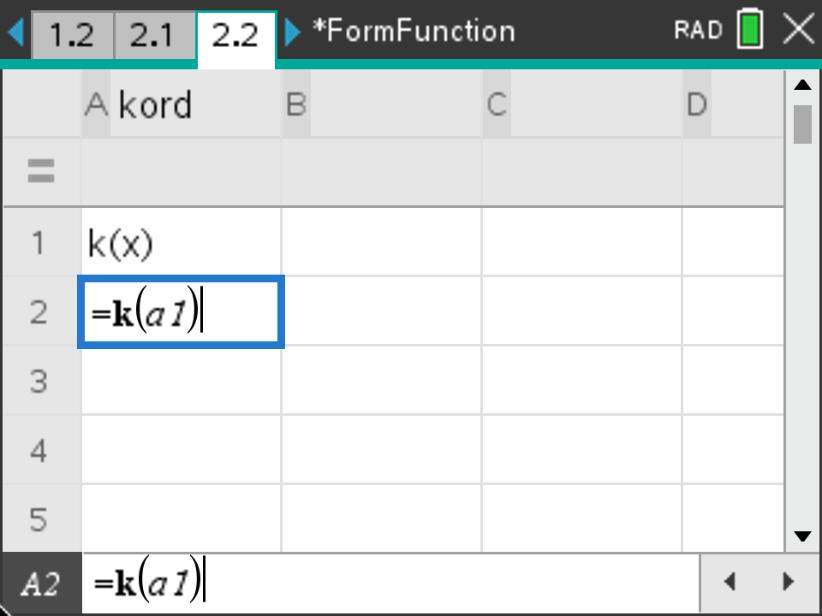

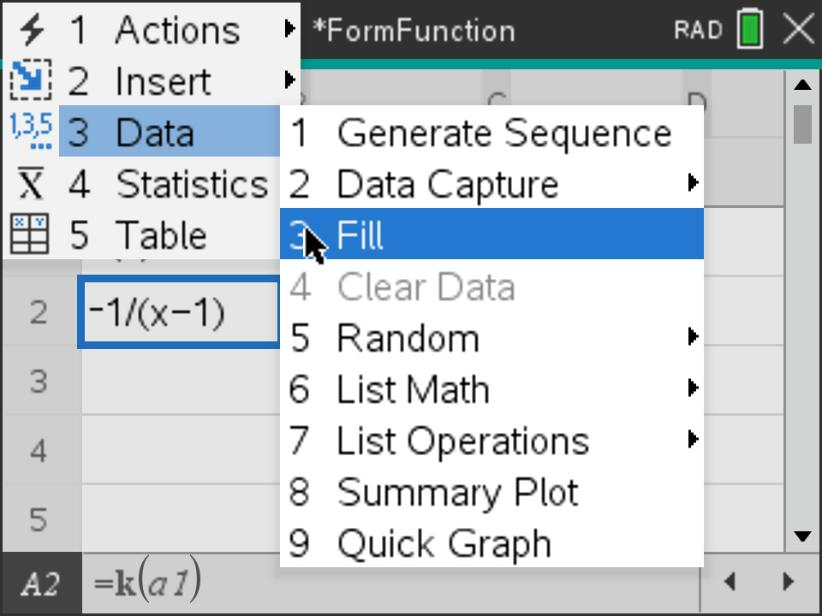

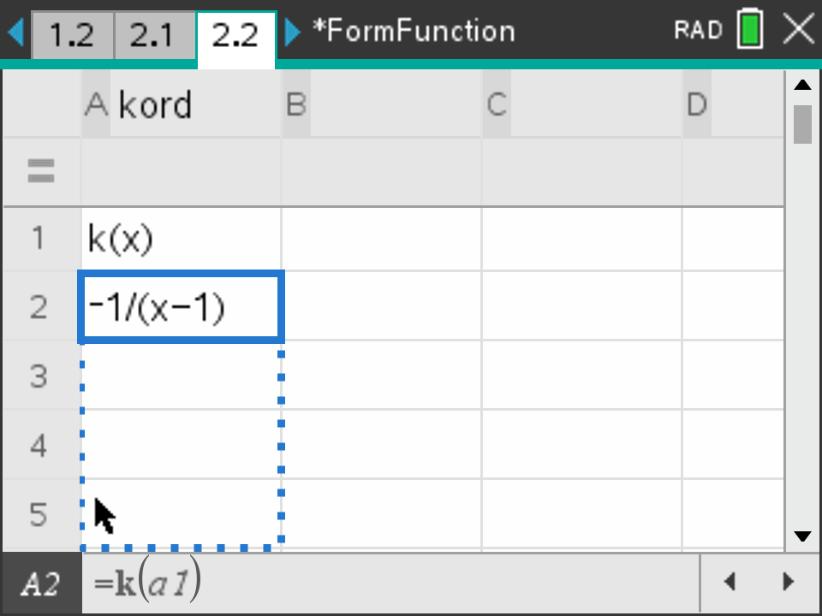

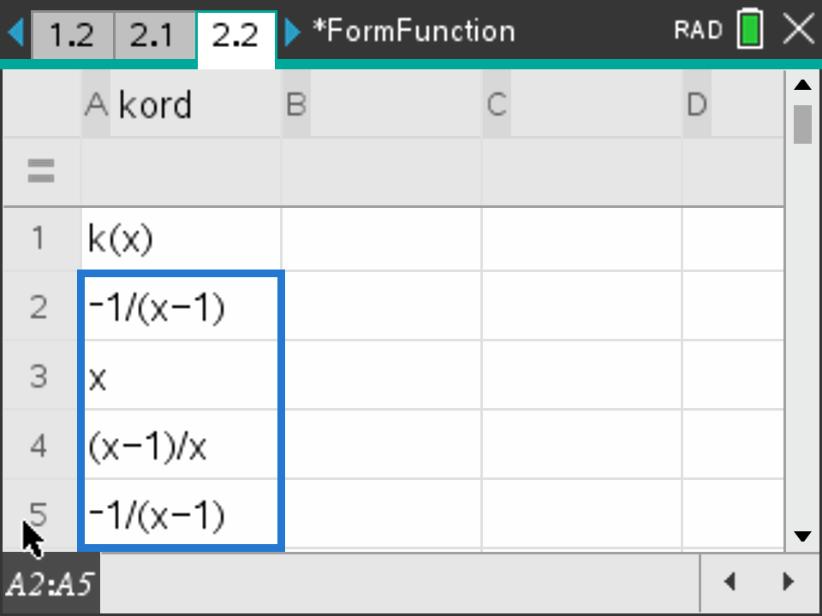

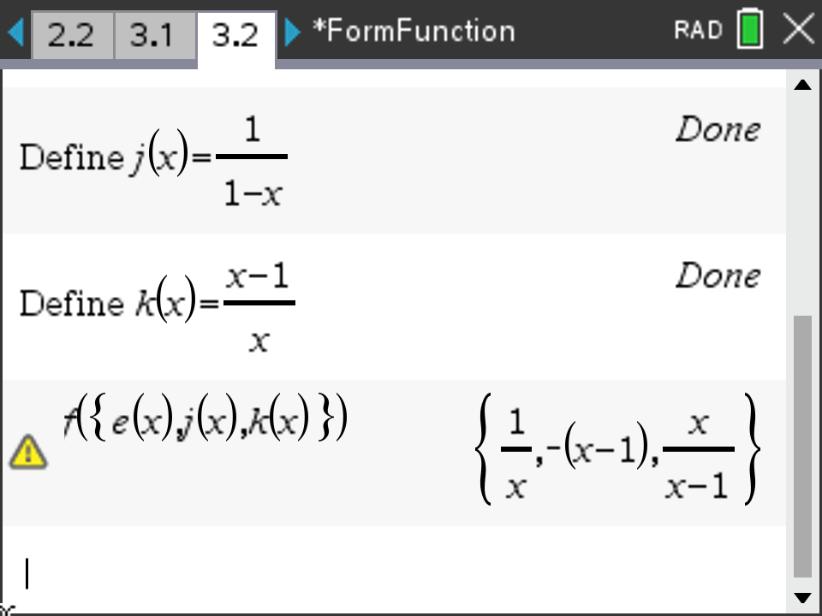

On page 2.2, use your algebraic spreadsheet to generate a sequence of \(k, k^2, k^3, \ldots, k^{10}\text{.}\) To do this, you can use the \(\mathbf{Fill Down}\) feature of the spreadsheet by first entering \(k\left(x\right)\) in the cell \(\mathbf{a1}\) and then in cell \(\mathbf{a2}\) entering \(=k\left(a1\right)\text{.}\) Then select cell \(\mathbf{a2}\) and choose menu \(\mathbf{3:Data}\) followed by \(\mathbf{3:Fill}\text{.}\) Using the down arrow key, move down in the spreadsheet about 8 cells or so and press enter· (See screens below for setting up the recursive composition). For what powers of \(k\) do you get \(k^n=e\text{?}\) Note that we labeled the column “kord” because this iteration will help us find what is called the order of the element \(k\text{.}\)

(k)

Using your algebraic spreadsheet to make a column for each function, repeat part (j) for the other functions in \(T=\left\{e,f,g,h,j,k\right\}\text{.}\) Label the columns “ford”, “gord”, “hord”, …etc. List the elements in each set produced. For example, in using the element \(k\text{,}\) you should get \(kord=\left\{k,j,e\right\}\text{.}\) You should notice that these elements just keep repeating and so the set is just limited to these three elements (note that when listing elements, we do not care about the order in which the elements are listed since they are just a set). Mathematically here we use the notation \(\langle k \rangle\) to mean the subgroup generated by \(k\) (i.e. repeatedly iterating \(k\) with itself \(\langle k \rangle=\left\{k, k^2, k^3, \ldots\right\}\)). In this case, \(\langle k \rangle\) is finite with order 3 since it begins to repeat. What can you say about the sizes of these subsets? Here the "size" or number of elements in the subgroup is called the order of the subgroup. State any patterns you notice.

\(\langle e \rangle=eord=\)

\(\langle f \rangle=ford=\)

\(\langle g \rangle=gord=\)

\(\langle h \rangle=hord=\)

\(\langle j \rangle=jord=\)

\(\langle k \rangle=kord=\)

(l)

List the smallest positive “power” for each element of \(T\) that yields, \(e\) [this is called the order of the element, denoted \(\lvert a \rvert\text{.}\) You can also think of this as the number of elements in the subsets produced in part (k)]. State any relationship you see between these powers and the number of elements in set, \(T\text{.}\)

\(\lvert e \rvert=\)

\(\lvert f \rvert=\)

\(\lvert g \rvert=\)

\(\lvert h \rvert=\)

\(\lvert j \rvert=\)

\(\lvert k \rvert=\)

(m)

Do any of the subsets found in part (k) form a group? If so, we call them subgroups because they are a subset that is also a group? Groups or subgroups that have this repeating pattern when generated by a single element are called cyclic. List all of the subgroups you find. Explain how you know each is a group.

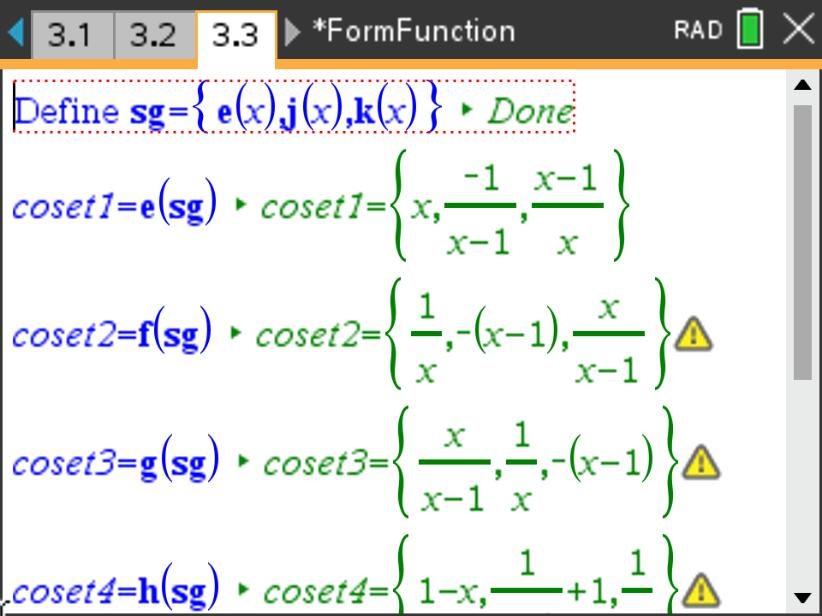

What do you think would happen if we composed a function not found in a specific subgroup with each element in that subgroup? To investigate this question, pick one of the subgroups generated in a column from part (k) and compose it with a function not in the subgroup. For example, using the subgroup \(\langle k \rangle=kord=\left\{e,j,k\right\}\) and composing the elements with, say \(f\text{,}\) we get the new set as shown below. This subset formed by composing \(f\) with \(\langle k \rangle\) is denoted \(f \circ \langle k \rangle\) and called a coset. This can be done in either the Calculator page or the dynamic Notes page as shown below. Note that for your convenience, the Notes page (3.3) allows you to edit the subgroup at the top of the page and all cosets below it are automatically updated.

(n)

How many elements are in our new coset, \(f \circ \langle k \rangle\text{?}\) Does the new coset form a subgroup? Use the Notes page (3.3) for composing the elements of \(\langle k \rangle=kord=\left\{e,j,k\right\}\) with the other elements from \(T\) not in \(\langle k \rangle\text{.}\) What do you notice? Describe what you observe if the other element is already in \(\langle k \rangle\) (e.g. compose \(\langle k \rangle\) with all elements from \(\left\{e,j,k\right\}\text{.}\) Explain why your observations would be true.

(o)

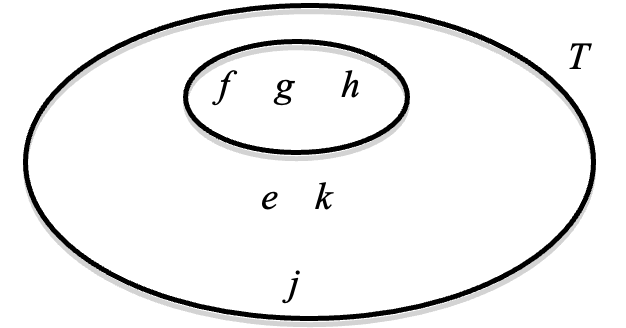

Consider the following diagram of the set, \(T\text{.}\) Draw a boundary around the cosets you found in part (n). An example of the boundary for the coset of the function \(f\) composed with the subgroup \(\left\{e,j,k\right\}\) is shown below. Describe what you notice about the coset boundaries you draw for each situation you found in part (n). Sketch a boundary around the resulting elements in \(T\) below.

(p)

Now repeat what you did in parts (m) & (n) using each different subgroup you found in part (k), sketching boundaries around the cosets formed in the composition of all of the elements from \(T\) with the subgroup. What can you say about the relationship among the cosets formed in each case?

(q)

Do all of the different cosets you found in part (p) form subgroups? If not, under what conditions do they form subgroups?

(r)

At this point our observations about the partitioning of a group into subsets is based solely on one example of a group. To test your conjectures, first confirm that the following set, \(S\text{,}\) of matrices forms a group under the operation of regular matrix multiplication. To do this, first insert a new problem by pressing doc and selecting \(\mathbf{Insert}\) and then \(\mathbf{Problem}\text{.}\) After selecting a Calculator page, use the Define command to store each matrix by name in memory so that product of, say \(a\) and \(b\text{,}\) can be entered simply as \(a\cdot b\) on the CAS. Now create subgroups of the set by raising each element to increasing powers until you reach the identity, then repeat the process from parts (o) and (p) to see if the group of matrices is partitioned in a similar manner as was the set \(T\) by sketching and circling subsets.

(s)

Using the evidence from your diagrams, give an argument for why the order of an element must divide the order of the group. Given that your argument is based on only a few cases of evidence (namely the sets \(T\) and \(S\) with various subgroups), what main properties would you need to show in order to prove your claim in general?

So what are the takeaways from this investigation, specifically for this particular set and operation, as well as for general structures that have the properties of groups? Well, let’s consider the observations you hopefully noticed in the exploration. We can summarize four main ideas here.

From part (k), the order (or size) of the subgroups were either 1, 2, or 3.

From part (n), all cosets were the same size as the subroup that generated the coset.

From part (p), cosets generated by a given subgroup are either completely identical or completely disjoint.

From part (p), all elements of the group occur in exactly one coset, disregarding repeated cosets (i.e. no stragglers lurking outside a coset).

The result of these observations is that the group gets chopped up into disjoint subsets (cosets) all having the same number of elements in them. Since the cosets all have the same size as the subgroup used to generate them, this means that the size (or order) of the subgroup must divide the order of the original group. Hence since our group of functions had order 6, we should only expect a subgroup to have an order that is a divisor of 6. Again, as you noticed in part (k), the sizes of the subgroups were 1, 2, or 3 (all divisors of 6). We can’t have a subgroup of, say order 5, if our group is of order 6 since 5 does not divide 6.

We have observed these patterns in the activity

Activity 4.3.6, but will this hold for all groups? In order to be certain, we need to prove it for all groups based on the basic properties of groups. Let’s start by trying to argue these observations a little at a time.

One of the key parts of the argument deals with having all cosets being of the same "size" (actually the size of the subgroup that generated the coset). To establish that this was not just a fluke in our activity, we need to consider what would happen if cosets were not the same size as the subgroup that gave birth to them.

Theorem 4.3.8. Coset "Size".

A left (or right) coset in a finite group contains the same number of elements as the subgroup that generated the coset.

Proof.

Suppose \(H \lt G\) (i.e. \(H\) is a subgroup of \(G\)). Further, let \(H=\left\{h_1, h_2, h_3, \ldots, h_m\right\}\text{.}\) Now we can form a left coset, \(aH\text{,}\) such that \(aH=\left\{ah_1, ah_2, ah_3, \ldots, ah_m\right\}\text{.}\) We can claim that all elements of this coset are unique since if not, we must have that \(ah_i=ah_j\text{,}\) for some \(i\) and \(j\) with \(i \neq j\text{.}\) But this would mean that \(a^{-1}ah_i=a^{-1}ah_j \Rightarrow\) \(eh_i=eh_j\text{,}\) and thus \(h_i=h_j\) and so \(ah_i \neq ah_j\text{.}\)

The next observation that we made in

Activity 4.3.6 was that if we put all of the cosets together, we ended up with the entire group (as evidenced in your diagrams of cosets).

Theorem 4.3.9. Union of Cosets is the Group.

Let \(H\) be a subgroup of a group \(G\text{.}\) Then the union of all left cosets of \(H\) gives the entire group \(G\text{.}\) In other words, \(G=\bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\text{.}\)

Proof.

Since every left coset consists of elements from \(G\text{,}\) then \(ah \in G\) for all \(a \in G\) and \(h \in H\text{.}\) Therefore, we have \(\bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH \subseteq G\text{.}\) Now, if \(b \in G\) and since \(e \in H\text{,}\) we can see that every element of \(G\) can be found in its respective coset, \(bH\text{,}\) since \(b=be \in bH\text{.}\) Since \(b \in G\text{,}\) then \(bH \subseteq \bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\) and thus, every element in \(G\) is also in \(\bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\text{.}\) Therefore, \(G \subseteq \bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\text{.}\) Since \(\bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH \subseteq G\) and \(G \subseteq \bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\text{,}\) we have that \(G=\bigcup\limits_{a \in G}aH\text{.}\) Note that this proof also works for right cosets.

The significance of this theorem is that a group can be formed by the union of all of its left (or right) cosets. But, could some of these cosets overlap in some way? If so, how can the elements from one coset overlap with another? Are there any restrictions on the overlap? You will recall experiencing this partitioning in

Activity 4.3.6 lab when you placed boundaries around the subsets from

\(T\) that you found as a result of composing subgroups with elements from the set

\(T\text{.}\) You will also recall from the activity that the subsets (cosets) did not appear to overlap once you placed the boundaries around them. Put another way, the subsets generated in the activity either had no elements in common or were identical. While our experiences have suggested that there is no overlap, we do need to address this issue of possible overlap from a more formal and absolute sense. Consider the following theorem.

Theorem 4.3.10. Coset Overlap.

Let \(H\) be a subgroup of a group \(G\) and let \(a,b \in G\text{.}\) Then we have that any two left cosets \(aH\) and \(bH\) either have no elements in common or are identical.

Proof.

Suppose \(c \in aH\) and \(c \in bH\text{.}\) This means that \(c=ah_1=bh_2\) for some \(h_1, h_2 \in H\text{.}\) Then we must also have that \(a=bh_2h^{-1}_1\text{.}\) This implies that for any \(h_3 \in H\text{,}\) we can express \(ah_3=\left(bh_2h^{-1}_1\right)h_3=b\left(h_2h^{-1}_1b_3\right)=bh_4\) for some \(h_4 \in H\) since \(H\) is closed. From this we can say that \(ah_3=bh_4 \in bH\) and thus every element in \(aH\) is also in \(bH\) implying \(aH \subseteq bH\text{.}\) By a similar argument, we also get that \(bH \subseteq aH\text{,}\) thus \(aH=bH\text{.}\)

We now have everything we need to address the observation that you made from

Activity 4.3.6. Recall that when you examined the “powers” of the function composition in the activity, there was an interesting observation made, namely, the orders of the elements (functions in this case) seemed to be a divisor of the order of the group. This brings us to a classic theorem known as

LaGrange’s theorem.

Theorem 4.3.11. LaGrange’s Theorem.

Let \(G\) be a finite group or order, \(\left| G \right|=n\text{.}\) If \(H \lt G\) (i.e. \(H\) is a subgroup of \(G\)), and \(\left| H \right|=m\text{,}\) then \(m \mid n\text{.}\)

Proof.

Let

\(G\) be a finite group and

\(H \lt G\) with

\(\left| G \right|=n\) and

\(\left| H \right|=m\text{.}\) Since

\(G\) is finite and each left coset of

\(H\) has

\(m\) elements by

Theorem 4.3.8 with either left cosets being identical or disjoint as shown by

Theorem 4.3.10, there must be a finite number, call it

\(t\text{,}\) of distinct left cosets of

\(H\text{.}\) Since every

\(a \in G\) is guaranteed to be in the left coset

\(aH\) and together the union of all left cosets gives

\(G\) as seen from

Theorem 4.3.9, this implies that

\(n=mt\) and thus

\(m \mid n\text{.}\)

Now that we have spent some time exploring basic properties in algebra through

Activity 4.3.6, we can start to examine how these structures relate to the secondary curriculum and how we can engage students in doing more than mimicking symbol manipulation without an understanding of the meaning behind the manipulation. As you discovered earlier, the most basic of structure in algebra is the

group since the properties of a group are the minimal needed for use in solving an equation that uses only one operation. Let’s now dig a little deeper into these ideas.

Subsection 4.3.3 Algebraic Structure: Digging Deeper

In order to address the underlying structure of mathematics, we will examine a basic skill that is taught in the secondary schools from an advanced standpoint. At this point, it is assumed that the reader has experienced the corresponding parts of this text including the activity

Activity 4.3.6 as well as the portions of the

Interactive Mathematics Program (IMP) titled,

Functions in Verse,

Linear Functions in Verse,

An Inventory of Inverses, and the Supplemental Problem,

Its Own Inverse. In addition, it is also assumed that the reader has discussed the vignette,

Inverse Functions: The Case of Tim (

Activity 4.3.5). These activities and curriculum materials are essential to give the reader a point of reference for this mathematical discussion on algebraic structure.

\(\mathbf{Operations}\) \(\mathbf{and}\) \(\mathbf{Their}\) \(\mathbf{Representations}\)

Before we begin an examination of algebraic structure and its relationship to the secondary curriculum, we first need to think about the basic components that make up different types of algebraic structures. Generally, when we think about algebra, be it at the secondary or undergraduate level, we have two basic components—a set and an operation or operations.

You may recall from your high school experience a great deal of time spent simplifying or solving expressions or equations that involved primarily the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In these cases, the operations were binary meaning that they took two elements in a set (say the real numbers) and returned another element from the same set. While the result of a binary operation does not have to be from the same set as the inputs, we will restrict our discussion to this case since it is the most familiar. For example, \(2+3=5\) takes the two numbers 2 and 3 and returns the number 5. Similarly with multiplication, \(2 \cdot 3=6\) takes the two numbers 2 and 3 and returns the number 6.

Although arithmetic operations are the basis of many people’s experience within the school setting, we can also think about non-arithmetic operations. Recall from your experiences in the activity, Form and Function, we used the operation of function composition. If you have ever worked a puzzle called Rubik’s Cube, you have performed other non-arithmetic operations. In this case you can describe clockwise rotations of various faces as well as a myriad of other moves that transform the cube from one state to another. As we will see, whether we use arithmetic operations or non-arithmetic ones, there is an underlying structure that becomes evident as we notice patterns of behavior for elements of the set with which the operations are associated.

\(\mathbf{Solving}\) \(\mathbf{Basic}\) \(\mathbf{Equations}\)

When we examine the solutions to basic equations, we notice a similar structure that occurs in all processes regardless of the binary operation being used. If we consider the solution to the equation \(a*x=b\) for any binary operation, \(*\text{,}\) the process used to find the solution is the same no matter what operation we choose. However, in order to use this process, there are some underlying assumptions that need to be stated.

Recall in

Activity 4.3.1 and

Activity 4.3.2 we determined the minimal properties needed to be able to solve an equation in one operation. These properties were what we used to define the most basic of algebraic structures, a

group (see

Definition 4.3.1). If we examined the steps used in the solution of each of these equations, we will noticed that the statements of properties and definitions as well as the order in which they were applied were identical. In fact, when I was writing these portions of the text, I simply copied and pasted the first solution into the document and then replaced all of the "

\(+\) operations with “

\(\cdot\)" and then all of the instances of "

\(-a\)" were replaced with "

\(\frac{1}{a}\)". When we think about writing this section of the text in this way, the algebraic structure becomes very clear.

\(\mathbf{Operations}\) \(\mathbf{and}\) \(\mathbf{Functions}\)

In order to study algebraic structure, we need to first consider the basic components that make up that structure. As we stated before, generally we think of sets and operations as the building blocks of an algebraic system. Young children become familiar with the concept of set from a very early age through the use of physical manipulatives, but what about operations? How do children view operations? One might argue that many children see arithmetic operations as physical actions that operate on sets of objects. After all, early development of the addition concept involves combining sets of objects.

Others might argue that many children see operations as a series of procedures to be performed using pencil and paper. Traditionally, in elementary school, a great deal of time is devoted to memorizing “addition facts” and “multiplication tables”. Of course, from a traditional point of view, knowing addition and multiplication facts is essential for mastery of the algorithms that follow. One goal of our existing curriculum is to enable students to compute sums and products efficiently and accurately. However, after observing children working on problems within a context, we have begun to question whether or not they make the connection between the earlier physical operations on sets and the arithmetic operations on numbers. In many cases, a child will be able to perform computations such as \(427 \div 3\) while at the same time struggle with a problem like:

Sue, Jan, and Amanda put equal amounts of money together and bought a large tub of candy containing 427 pieces. If they agree to split the candy equally, how many pieces does each get? Are there any pieces left over?

In many instances, the child is able to do the computation when posed simply as, \(427 \div 3=\text{,}\) but does not necessarily have a conceptual understanding of what the quotient, remainder, or divisor represent. This disconnect between conceptual meaning and algorithmic procedure is concerning since in order to apply mathematical processes to real-world problems, the student must first understand what the process means so that it will be applied in an appropriate situation.

For example, in my early years of teaching, I has an experience teaching algebraic concepts related to distance, rate, and time. I asked a student the question, “If you drive at 55 mph for two hours, how far have you traveled?” Upon first consideration, the student simply looked puzzled. In response, thinking the student was having trouble doubling 55, I changed the problem by saying, “Suppose you drive at 60 mph for two hours, how far have you traveled?” \(-\) I thought doubling 6 might be easier. The student replied, “Three miles.” What was the student doing? Upon further probing, it turns out that the student was simply dividing 60 by 2 (incorrectly) because he had been taught that you “divide when you have distance, rate, and time problems.” It comes as little surprise that this same student when posed with a new problem and asked how he might solve it responded, “Add…, no subtract…, no divide.” After uttering each response, he would watch my face looking for cues as to which operation was correct. I referred to this student approach as the “random operator generator”. It is important to note that this student was fairly proficient at computing with pencil and paper algorithms. The bottom line is that this student had very weak (if not nonexistent) connections between algorithmic procedures and conceptual understanding of the operations in question. If unable to make conceptual connections, there is very little chance that the student will be able to solve mathematical problems. So what good is computational proficiency, if the student does not know when it is appropriate to employ a certain type of computation?

Functions, Mappings, and Binary Operations

As we think about teaching children operations and the algebraic properties that are associated with them, it is helpful to put ourselves in the same unfamiliar position as our students by considering operations that are not familiar to us. But how do we create operations other than addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division? We could use operations from linear algebra where properties such as commutativity are no longer assumed. However, we can also create our own operations that are combinations of familiar ones. Once created, we can then investigate properties and even attempt to solve equations that use the operation.

Suppose we want to explore a binary operation, call it \(*\text{,}\) on the set of real numbers defined by \(a*b=a+b-a\cdot b\) where "\(+\)" and "\(\cdot\)" are the familiar operations of addition and multiplication. It would be nice if we could define this operation and then explore it using technology. In order to do this, let’s first consider viewing a binary operation in a different way. As we discussed earlier, a binary operation takes two inputs, in this case from the set of real numbers, and yields a result that it also a real number. In algebra, we have seen another construct that also behaves in this manner (especially if we thinking back to Calculus 3). In a sense, a function takes inputs and produces outputs associated by the function rule. In this situation we want two inputs to yield a single output and so we can use a function of two variables. Here we can let a function, call it \(\varphi\text{,}\) be defined such that \(\varphi : \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(\varphi : \left(a,b\right) \mapsto a+b-a\cdot b\text{.}\) In this case, \(\varphi \left(a,b\right)\) acts like the binary operation \(a*b\text{.}\) The advantage of using a function approach to representing a binary operation is that we can use it to define the operation on a computer algebra system (CAS) and then explore the properties of “\(*\)” via the symbol manipulation capabilities of the CAS.

Activity 4.3.7. Using Binary Operations.

In this activity, we will explore a binary operation for which we have little intuition. This will allow us to focus on the meaning of algebraic properties more deeply since we cannot use our "common knowledge" to skip over how objects in a set (like the real numbers or integers) behave because we are too familiar with their behavior.

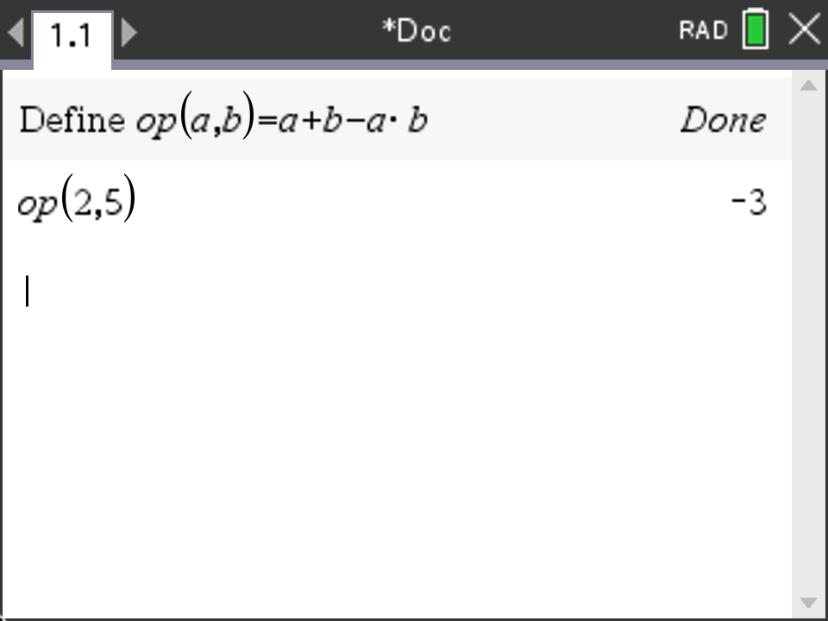

To begin, we are going to define the binary operation, \(*\text{,}\) that was describe above on our CAS so that we can manipulate expressions more easily. To do this, let’s define the operation by using a function of two variables calling it \(op\left(a,b\right)=a+b-a \cdot b\) as shown below.

(a)

Using your defined operation, \(*\text{,}\) on your CAS, explain whether or not it meets the first property of a group, closure. You may want to try to compute several cases like the one shown above for \(2*5=-3\) to convince yourself one way or the other. Can you think of a case where it would not be closed for the integers? For the real numbers? Explain your reasoning.

(b)

Assuming we are using the real numbers, \(\mathbb{R}\text{,}\) as our set, compute several cases like \(2*\left(3*5\right)\) and \(\left(2*3\right)*5\) to give some evidence of whether or not the operation, \(*\text{,}\) is associative. If it is, provide an argument to show it will be for any \(a,b,c \in \mathbb{R}\text{.}\)

(c)

Determine if \(\mathbb{R}\) has an identity element for \(*\text{.}\) If it does, what is it?

(d)

Determine if all elements of \(\mathbb{R}\) have an inverse under the operation \(*\text{.}\) If so, does \(\left(\mathbb{R}, * \right)\) form a group? If not, can you slightly adjust the set \(\mathbb{R}\) so that it does form a group? Explain your reasoning.

(e)

Think back to basic operations like multiplication or addition with real numbers. Have you seen any type of operation that needs a slight adjustment in order to form a group? How does is the behavior from part (d) similar? How is it different?

Exercises 4.3.4 Exercises

1.

Using your CAS and defining \(a*b=a+b-a \cdot b\text{,}\) find the solution(s) to the following equations. Be certain to state your CAS-defined operations and the commands you used to find the solution.

(a)

\(3*x=-9\)

(b)

\(\left(7*x\right)*y=-35\) and \(3*x=-11*y\)

2.

Consider the operation \(*\) given by \(a*b=a+b-5\text{.}\) Verify or refute the following properties. Assume the set under this operation is the set of real numbers. You may need to decide to restrict the set based on what you discover regarding the operation and its relationship to the properties (and a desire for it to be a group). If so, please explain your reasoning for the restriction.

(a)

Closure

(b)

Associativity

(c)

Identity

(d)

Inverses

(e)

Commutativity

3.

Consider the operation \(*\) given by \(a*b=\text{max} \left(a,b\right)\text{.}\) Verify or refute the following properties. Assume the set under this operation is the set of real numbers. You may need to decide to restrict the set based on what you discover regarding the operation and its relationship to the properties. If so, please explain your reasoning for the restriction.

(a)

Closure

(b)

Associativity

(c)

Identity

(d)

Inverses

(e)

Commutativity

4.

Use your CAS to show that \(G=\left\{

\begin{bmatrix}

a \amp b\\

-b \amp a

\end{bmatrix} \mid a,b \in \mathbb{R} \text{ and not both zero} \right\}\) is a group under matrix multiplication. Further, show that \(G\) also has the property of commutativity. A group that is also commutative is called abelian.

5.

Show that the set of 8 symmetries of a square (four rotations and 4 flips) is a group.

6.

Consider \(SL\left(2, \mathbb{R}\right)\) which is defined to be the set of all \(2 \times 2\) matrices of the form \(\begin{bmatrix}

a \amp b\\

c \amp d

\end{bmatrix}\) such that \(a,b,c,d \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(ad-bc=1\text{.}\) Show that \(SL\left(2, \mathbb{R}\right)\) is a group under matrix multiplication. This is called the special linear group—hence the “SL” in the notation.

7.

Suppose that \(G\) is a group and \(a,b,c \in G\text{.}\) Show that if \(ab=ac\text{,}\) then \(b=c\text{.}\)

8.

Suppose that \(G\) is a cyclic group. Explain why it must therefore be abelian. Note that if a group is cyclic, there must be at least one generator (i.e. an element for which all elements in \(G\) can be expressed as a power of it).

9.

Create a set of 8 complex numbers that form a cyclic group under multiplication and identify all elements of the group that are generators.

(a)

List all elements and their inverses.

(b)

Find the orders of each element of the group and describe any patterns you notice with respect to their inverse’s order.

10.

Let \(G=\left\{

\begin{bmatrix}

a \amp a\\

a \amp a

\end{bmatrix} \mid a \in \mathbb{R}, a \neq 0 \right \}

\text{.}\) Show that \(G\) is a group under matrix multiplication. Explain why each element of \(G\) has an inverse even though the matrices have determinants of 0.

11.

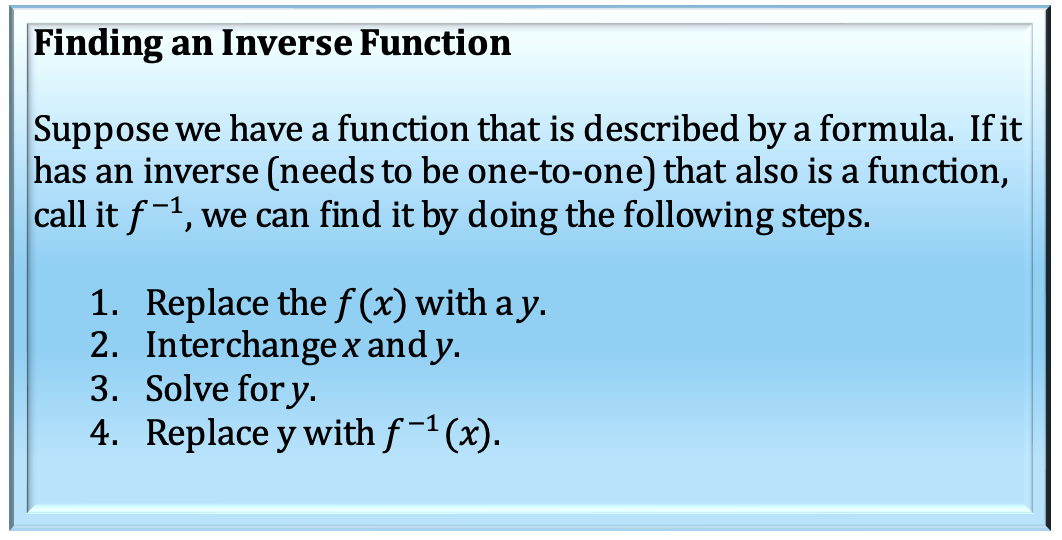

Consider the following activity from the High School curricula, Interactive Mathematics Program (IMP), 4th year text, Its Own Inverse (IMP, 2000, p. 155).

In Linear Functions In Verse, \(f\) was an arbitrary linear function defined by the equation \(f\left(x\right)=ax+b\) (with \(a \neq 0\)). You needed to find an expression for \(f^{-1}\left(x\right)\text{.}\) Which linear functions are their own inverses? That is, for what choices of \(a\) and \(b\) is \(f\) equal to \(f^{-1}\text{?}\) (Note: There are infinitely many possibilities.)

12.

Consider the invertible function, \(f\left(x\right)=x^3+2\text{.}\)

(a)

In words, describe what you would do with an input for \(f\) to evaluate it at that value.

(b)

Using your words from part (a) and the process of "undoing", give an expression for \(f^{-1}\text{.}\)

(c)

Graph both \(f\) and \(f^{-1}\) on the same axes. Describe any symmetry you see with these graphs.

(d)

How can the graphical relationship you see in part (c) help with answering exercise 11? Does it support your responses to exercise 11? Explain.

(e)

Examining your experiences in

Activity 4.3.6, does this graphical observation support what you found for elements of order 2? Explain.